Beyond Piketty's Capital

What Ben Franklin and Billie Holiday Could Tell Us About Capitalism’s Inequalities

It has now been two years since French economist Thomas Piketty published his tome, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, and one year since it was published in English, raising a fanfare of praise and criticism. It has deserved both, most notably for “putting the distributional question back at the heart of economic analysis.”[1] I would imagine Professor Piketty is also pleased by the attention his work has garnered: What economist doesn’t secretly desire to be labeled a “rock-star” without having to sing or pick up a guitar to demonstrate otherwise?

Piketty’s study (a collaborative effort, to be sure) is an important and timely contribution to economic research. His datasets across time and space on wealth, income, and inheritances provide a wealth of empirical evidence for future testing and analysis. The presentation is long, as it is all-encompassing, tackling an ambitious, if not impossible, task. But for empirics alone, the work is commendable.

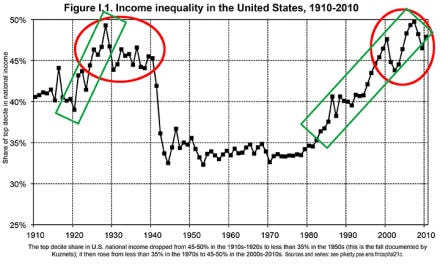

Many critics have focused on methodology and the occasional data error, but I will dispense with that by accepting the general contour of history Piketty presents as accurate of real trends in economic inequality over time. And that it matters. Inequality is not only a social and political problem, it is an economic challenge because extreme disparities break down the basis of free exchange, leading to excess investment lacking productive opportunities.[2] (Piketty ignores the natural equilibrium correctives of business/trade cycles, presumably because he perceives them as interim reversals on an inevitable long term trend.) I have followed Edward Wolff’s research long enough to know there is an intimate causal relationship between capitalist markets and material outcomes. I believe the meatier controversy is found in Piketty’s interpretations of the data and his inductive theorizing because that tells us what we can and should do, if anything, about it. Sufficient time has passed for us to digest the criticisms and perhaps offer new insights.

Read the full essay, formatted and downloadable as a pdf...

-----------------------

[1] Distributional issues are really at the heart of our most intractable policy challenges. Not only are wealth and income inequalities distributional puzzles, so are hunger, poverty, pollution, the effects of climate change, etc. Unfortunately, the profession tends to ignore distributional puzzles because the necessary assumptions of high-order mathematical models that drive theory rule out dynamic network interactions that characterize markets. Due to these limitations, economics is left with the default explanations of initial conditions, hence the focus on natural inequality, access to education, inheritance, etc. General equilibrium theory (GE) also assumes distributional effects away: over time prices and quantities will adjust to correct any maldistributions caused by misallocated resources. For someone mired in poverty or hunger, it’s not a very inspiring assumption.

[2] As opposed to distributional problems, modern economics is very comfortable studying and prescribing economic growth. Its mathematical models provide powerful tools to study and explain the determinants of growth. This is why growth is often touted as the solution to every economic problem. (When you’re a hammer, everything looks like a nail.) But sustainable growth relies on the feedback cycle within a dynamic market network model, so stable growth is highly dependent on sustainable distributional networks.