Social Behavior and the Coronavirus Pandemic

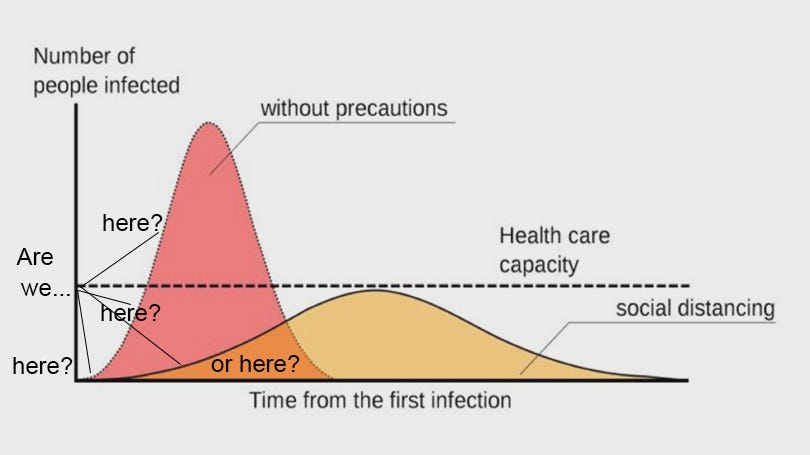

If you’re like me and follow the mainstream as well as social media, you’ve likely been inundated with information about the coronavirus pandemic, with many different data interpretations and conflicting claims based on these interpretations. The simple graphic below, called “flattening the curve,” seems to be the dominant visual for explaining the current public healthcare issues and provides a good starting point.

The graph was created by disease specialists at the CDC and has been spread widely by medical professionals, government officials, and non-government agencies. It visually represents the logic behind the political response to the crisis and the strategy to slow the spread of the virus. This is critical to managing the capacity limitations of healthcare resources like hospitals, drug therapies, and healthcare personnel. However, it is a theoretical model based on exponential pandemic dynamics; it is not a graph of actual empirical data. It is meant to educate, not report.

Unfortunately, the graph has been adopted by public media as a projection of “likely” real-time scenarios under various assumptions, focusing completely on the rose-colored part of the graph. According to this worst-case scenario, without strict adherence to isolation protocols the coronavirus is projected to spread exponentially through the population, placing an impossible burden on healthcare resources. The problem is that the empirical data so far does not seem to be supporting this worst-case scenario.

Let’s not get derailed here: the virus outbreak is a serious public health threat and a deadly threat to the elderly and immune-compromised. Our policies should foremost target the security of these groups. In this respect, the model is valuable and instructive, but not so much for actual health outcomes to the majority of the population. From the macro point of view, we have little idea how many of those people infected will require medical intervention and how extensive that intervention might be. In other words, infection rates may not impact health care capacity as depicted here. We also have little feel for how high or low that spike might be, or the magnitude of the y-axis – is it thousands, millions, or billions? 20%, 50% or 90%? Many media interpretations of existing data choose a scale that looks like we’re shooting up to the top of that rosy peak when we are really barely past the initial stage way, way down near the floor of the x-axis (see next graph). The projections repeatedly fail to project for interventions and behavior changes.

Also, as we discover more and more people have contracted the virus yet show no serious symptoms, we are missing any projection of herd immunity. Immunity gradually reduces the ability of the virus to find new hosts within the existing population so it gradually dies out.

What is valuable about the meme is the implication for how the public should adapt social behavior now to reduce the transmission rate of the contagion. Physical or social distancing is at this time imperative. Essentially this is less about biology and more about social behavior informed by biology. It strikes me that most of our media information is overly focused on very uncertain medical data given credibility by concerned medical experts. The problem is that the experts are shrouded in uncertainty and thus must err on the side of extreme caution. In hindsight most of this speculation will likely turn out to be fictional. But the effect will be real, and this takes us back to social behavior.

Some reports opine that this coronavirus is just a bad flu. If one is looking at medical data, I would tend to agree. But looking at social behavior, I would obviously disagree. What is driving social behavior, which will be measured in political policies and economic results, relates to the nature of this pandemic, not the pathogen itself. The coronavirus strikes at the heart of our instinctual behavior in the face of existential threats.

The real problem we face is that 1) the threat is invisible, 2) seems to be highly transmissible and somewhat random, 3) offers no preventive therapy (vaccine) or 4) sure treatment options or cures. Thus, 5) we feel little sense of control over what might be a serious existential threat. What this combination of characteristics does is incite a strong psychological reaction to uncertainty, risk, and potential loss, leading to exaggerated reactions to very low probabilities.

We know from behavioral science that the survival instinct causes behavior to respond to these contextual parameters. Humans, like all sentient beings, are risk and loss averse. Loss pertains to the nature of the threat, such as will I lose my job, or my savings and pension, or the ultimate existential threat: will I get sick and die? Risk is a probability function of the uncertainty of that loss. As the threat level rises (reported death counts and mortality rates) people become more fearful. Then, as uncertainty blankets us like a fog, the anxiety level rises. This survival response is perfectly rational for any organism trying to stay alive.

The important thing to note is that when the probability of loss increases and the consequence becomes more serious, people tend to become risk-seeking. In other words, faced with a likely existential threat, people take more behavioral risks than would be rational in the absence of that threat. We see this in those apocalyptic movies, when widespread hysteria and panic leads to chaos and deadly conflict, where more people die from the chaos than from the threat.

Individual behavior is compounded by irrational social behavior. An example is the panic buying of paper products, where some people, pressed to explain their behavior, have only offered the justification that everybody else was hoarding paper, so they were too. This suggests that what may not be categorically much different than a bad flu medically has the potential to turn into a global social and economic crisis.

So why is this reaction to coronavirus different than the Asian bird flu, Ebola, SARS, MERS or H1N1? The coronavirus seems to have a much higher and faster transmission rate than these previous pathogens and thus it has spread world-wide much faster. This is likely because it is highly asymptomatic while it is contagious and spreading. It also may be far more benign. But we don’t know why it is asymptomatic in some people and severely life-threatening for others. This uncertainty and randomness heighten our fear of the threat.

There is something else going on with the present pandemic that is aggravating the crisis. Because the virus has easily spread rather quickly, our global information media has gone into overdrive, especially social media. We know that social media is mostly driven by emotional reactions to uncertain facts, what we now call fake news. The sad reality is that the traditional print and broadcast media have also had to succumb to sensationalism and emotions in order to stay in business. Remember the editor’s dictum: If it bleeds, it leads. This presents the danger of reporting one random healthy young person who dies of COVID-19 complications instead of the thousands of others who contract the virus and seem unaffected. Our media, willingly or unwillingly, by focusing on infection and death counts taken out of context may be contributing to the social psychological effects driving this pandemic crisis. Worst-case scenarios painted by the medical experts and spread by the media are doing the same.

I suspect officials may sincerely believe projecting the worst-case scenario is necessary to “scare people straight” to get them to change behavior. But social behavior indicates that fear can become more viral than the virus, increasing the threats to social stability, safety, and security.

If one doubts this, imagine what would happen if a vaccine or cure were discovered tomorrow. Most of the world would return to normal the next day, not because the pathogen was eradicated any more than the seasonal flu, but because our fear would disappear.