This is the second installment of this three-part essay. Part One is here.

PART TWO

I. The Consequences of Money Illusion (or The Wages of Sin)

The costs and benefits of money illusion are not equally shared across society or across countries in the global economy. This creates dangerous imbalances in financial markets, economies, social relations, and national and international politics. We’ll address some of the principal areas of tension.

A. Price Distortions

Money is the measuring stick of value while nominal prices are the information signals of relative value. This is profoundly important. Prices tell us what to buy when, whether to consume now or later, where to invest resources, how to budget our resource allocations over time. Without accurate prices we are essentially flying blind financially. Profits as a function of nominal price indicators are also critical information signals that tell us where to invest and whether we are digging ourselves into a financial hole or ascending the next mountain top. This was the great insight of Friedrich Hayek in his critique of central planning.[1]

Experiments in central planning, such as those in the USSR and Mao’s China, eschewed price and profit/loss signals, wrongfully attributing them to capitalist exploitation rather than a return to competitive risk-taking enterprise and a signal of productivity. On a national scale the inefficiencies resulted in economic decline that led to the collapse of centrally planned economies and the dissolution of their political regimes. While the Western capitalist societies still rely on market pricing, money illusion distorts prices and obscures true value with the results being greater inefficiency, waste, and declining economic growth.

The problem runs deep because money illusion targets the level of interest rates, which represent the one true price that governs the macroeconomy and financial markets over time. The one true price because everything else in the market economy keys off the notional interest rate.[2] In the US, this is the Federal Reserve’s Funds Rate that sets the rate at which member banks can borrow from the Fed to cover their liquidity and reserve requirements.

The interest rate is the price signal that calibrates the risk-adjusted return to waiting. In other words, it tells us how much to consume today rather than deferring consumption to save and invest for the future. This allows the economy to find the equilibrium between consumption, saving, investment, and production over time. This is crucial to understand. Imagine a seesaw where the left side is present consumption and the right side is future consumption. The interest rate is the fulcrum that balances the seesaw. As rates move lower to the left, the level of present consumption goes up while future consumption falls. When the rate moves higher to the right, present consumption falls and future consumption (based on growth) goes up. Whatever is not consumed, i.e. deferred, is saved and invested.

Another useful analogy is the farmer’s seed corn. If his family eats all the corn today, there will be no seed and no crop next year and they may starve next winter; but if he saves all the corn seed for next year, his family may starve this winter. The idea is to find the equilibrium between present and future consumption that depends on demographic demands and investment prospects (usually technological innovations).

Another way to view the Fed’s interest rate manipulation is to realize what the interest rate means in existential terms. A low or declining interest rate is telling us to consume more now because the reward for waiting is low. A high or increasing interest rate tells us to defer consumption in order to save and invest to produce more growth and increase our consumption in the future. When we distort the interest rate we are sending the wrong signals that confuse market participants as to how to allocate their resources most efficiently. This distortion rewards inefficient behavior, depressing long-term economic growth and opportunity.

Think about the existential signal that 10 years of zero interest rate policy was telling markets: there is no tomorrow. That is certainly not the path to prosperity, and yet it persisted for more than a decade. ZIRP is the sign of a very sick economy that needs to get back on its feet ASAP, not languish for years.

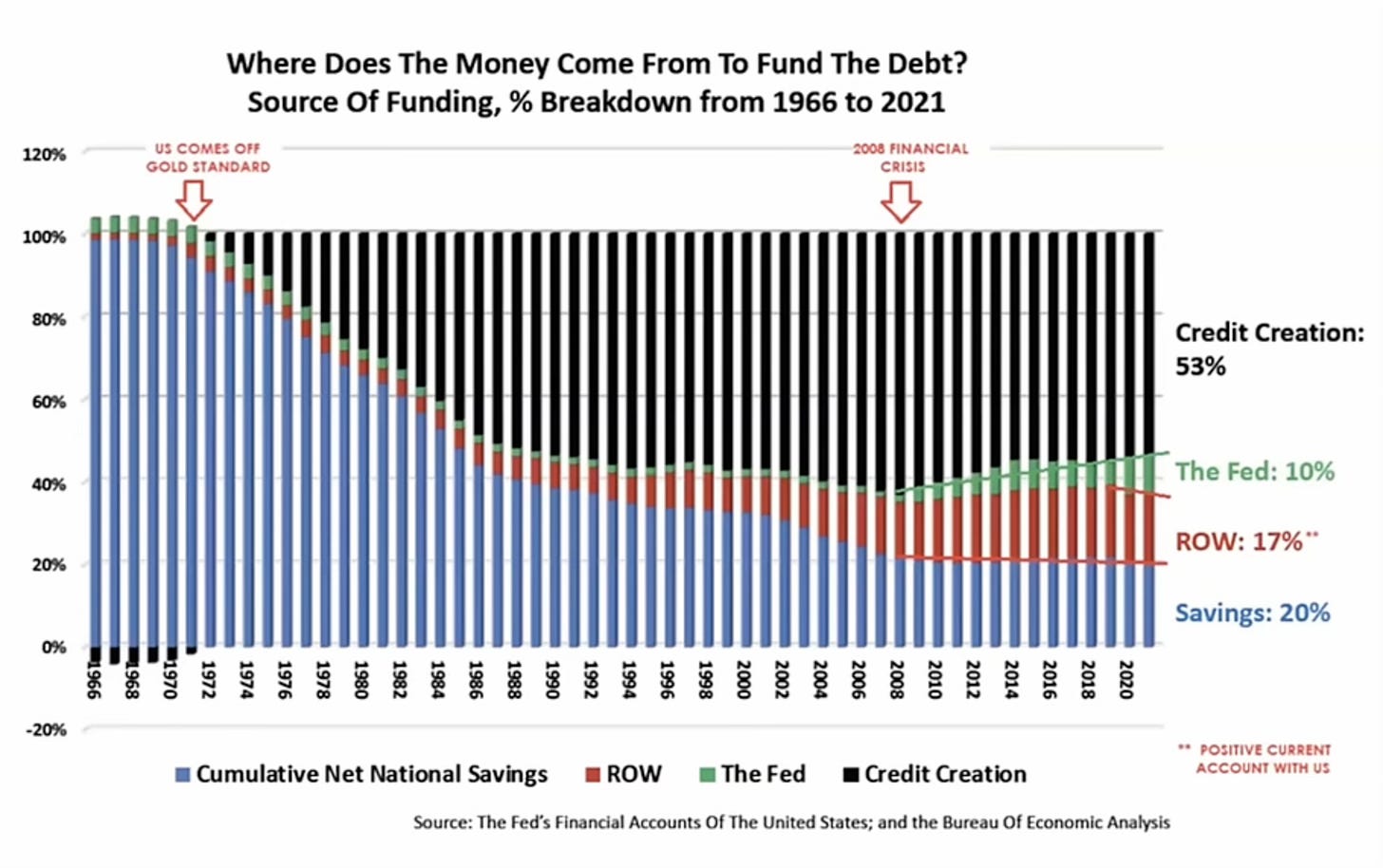

Under a fiat currency system, central banks are able to suppress interest rates causing excess consumption, inadequate saving and investment, and lower long-term growth. It allows governments to borrow and deficit spend with impunity. As I explained above, such policies favor a short-term boost to consumption demand at the cost of sustainable real growth. In recent years, this subsidized credit bubble has led to the accumulation of massive debt burdens, especially in the public sector.

The immediate consequences of such monetary mismanagement were mitigated by globalization and trade liberalization, whereby large economies and labor forces were unleashed. China and India were the major actors with almost two billion workers entering the global workforce. Having complete government control over banks, the Chinese government then invested the savings of this new, productive workforce into funding US Treasury borrowing by buying US government bonds. This encouraged greater deficit spending by the US government that ended up in the hands of US citizens to consume more cheap foreign manufacturing products, primarily from China. Thus, imports of cheaper Chinese goods depressed inflationary forces, enabling the Fed and Treasury to continue subsidizing US consumption and investment.

Since the pandemic, China and other central banks have reduced their purchases of US bonds, leading the Fed to become the default buyer of US Treasuries and other credit instruments like mortgage bonds. The excessive stimulus spending and monetization in response to the pandemic led to the spike in inflation to just over 9% in 2022. The burdens of inflation mostly fall upon the shoulders of consumers in the lower income, working, and middle classes, further aggravating the massive wealth transfer from the bottom 90% to the top 1%.

B. Asset Bubbles and Inequality

Fiscal and monetary policy in the US is transmitted through the banking system, then through the securities markets. Loans to the private sector, i.e. Main Street businesses and mortgage borrowers, are at the discretion of bank lenders. Weighing the risks of lending vs. the risk-free returns offered by the Treasury or Fed reserves means banks may choose to just funnel the funds back into Treasury bonds. In effect, banks could borrow at 0% (the Fed’s Zero Interest Rate Policy, aka ZIRP) and then buy long term Treasury bonds yielding 3% at zero risk. Why lend to risky businesses? So much of the subsidized credit and debt ends up circulating through the financial system, bidding up the prices of financial and real assets. Naturally this benefits those who own those assets to the detriment of those who don’t – it’s the haves getting rich to the detriment of the have-nots struggling with repressed wages and savings.

These policies continued off and on for almost three decades, causing the greatest wealth transfer from the 90% to the 1% of the richest members of society since the Gilded Age, estimated to be roughly $50 trillion from 1975 to 2018.[3]If income distributions had remained constant over this period, the median annual incomes of the 90% would have doubled in US$ terms, from $55,000 to $110,000.

At the same time as asset prices were exploding—especially financial assets and housing, but also education, insurance, and healthcare—savers and lenders were subject to financial repression with zero to negative interest returns on their investments. Inflation as registered by the Consumer Price Index was restrained by globalization and failed to reflect the massive price increases in the true cost of living. Cost of living adjustments (COLAs) to wage contracts are calibrated off the CPI numbers rather than true inflation as reflected in the decline in purchasing power of the US$ that has been estimated north of 12-15% after asset prices are factored in. Think of the consequences for the retiree living on fixed interest income, or pension funds relying on risk-free returns, or working families trying to save for a house or car. The banking and financial system and those associated with it were essentially being subsidized by the poorest members of society. These are just some of the wages of the policies and politics of money illusion.

Risk, Volatility, and Uncertainty

Excess money and credit floods money liquidity into the financial system. This excess liquidity sloshes around looking for places to invest with higher potential returns. The explosion of foreign exchange trading that occurred when rates began to float after 1971 caused greater volatility in price action providing opportunities for speculation. This speculative financialization of asset markets soon spread to housing, business and auto loans, precious metals, and stocks and bonds. Excess liquidity was funneled to new business start-ups in the venture capital industry, causing a boom in the technology sector regardless of profitability. The lack of credit restraint has led to more speculative activity across all markets, increasing volatility, hidden risk, and uncertainty. The opportunities to exploit volatility led to the sudden rise of sleepy hedge fund and private equity industries to take a dominant role in the investment world. Instead of making things, we have promoted financialization, speculation, trading, and arbitrage.

But the lack of credit restraint also has a profound effect on peoples’ behavior and incentives. The financial economy begins to run on irrational exuberance as market prices depart from fundamental value measures. The speculative behavior becomes a contagion as people adopt YOLO and FOMO and soon people are bidding millions of US$s on digital renderings of bananas and cats. But such behaviors introduce systemic risks into markets, abrogating the proper role of finance to mitigate and manage risk. Debt leverages and concentrates risk, while securitization of debt instruments can obscure these risks while making them more acute and contagious. We saw the consequences of this with the Great Financial Crisis of 2008/9, when securitized mortgage loan markets became the tail that wagged the dog of the global financial system. Since then we have doubled and tripled down on the exact behaviors that destabilized the system in the first place. When returns are decoupled from risks, the incentive to manage those risks is dissipated, creating dangerous hidden systemic risks. This is a precarious situation to be in, but it gets worse.

C. Money and Trust

Democracy is based on the principle of a social contract between the citizenry and those governing institutions meant to serve the public good. Citizens willingly give up some individual freedoms in exchange for the protection and benefits of a society governed by laws and executed by their elected leaders, allowing for a system where people can hold those leaders accountable and participate in decision-making through democratic processes. This arrangement implies a level of trust between the citizens and their elected leaders to fulfill the spirit of that contract.

The US$ is a Federal Reserve Note, a form of promissory note, just like a loan contract. As it says on the bills, “This note is legal tender for all debts, public and private.” Money represents the material contract between the government and its citizens concerning all taxes, benefits, and payments. At times this promissory note could be redeemed for gold and/or silver. A solid silver US dollar represented its weight in silver priced at $1 at the time of issuance is now worth roughly $31/oz. Under the gold convertibility standard after 1900, the US paper dollar was a promise that could be redeemed from the US Treasury for gold at the rate of $35 per oz. This convertibility ended in 1933 and was made available again under the Bretton Woods accords in 1948, but only for foreign treasuries. Now an ounce of gold will cost you roughly $3,000. Today the US$ is only backed by “the full faith and credit of the United States government.” However, under a fiat currency regime, certifying the material true value of that promise is subject to manipulation over the money supply. So, what is a US$ worth? It’s worth whatever you can trade for it and that will vary from day-to-day. This is where money illusion enters our lives.

There is a well-worn saying proclaiming that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. The same can be said about the power derived from money and wealth. I might rephrase it as money corrupts and free money corrupts absolutely. When borrowing rates are at or below the inflation rate, money is essentially free – the rational thing to do it to borrow as much of it as one can to leverage the purchase of real assets. Some groups in society benefit far more than others.

As explained above, the primary beneficiaries of free money operate in the financial sector that includes investment bankers, traders, hedge funds, private equity, venture capitalists. Next in line are politicians, public officials, public sector unions, the real estate industry, large corporate management, growth industries like technology, and cultural elites. Those most hurt by money illusion are savers and lenders, wage earners, small Main Street businesses, taxpayers, retirees, and the poor. This second group comprises the majority of voters in a democratic society. We can easily see the wealth divide widen between these winners and losers and how that has fractured politics and our sense of justice under the democratic social contract.

Attitudes across the population reflect this fraying of the social contract. An opinion survey that has tracked public trust in government since 1958 shows a steady decline from near 80% after the Kennedy administration to its nadir in 2023 when only 16% of respondents said they trusted the government just about always or most of the time, the lowest measure in nearly seven decades of polling.[4]

This mistrust extends across the board to Congress, the political parties, the justice system, the media, the educational system and, after the pandemic and environmental hyperbole, even to the healthcare and scientific communities. Certainly, this mistrust is partly due to the rise of the too-much-information age, which has given way to the “misinformation age,” but what money illusion has done is damage the integrity of society’s leadership elites by distorting their financial incentives and civic responsibilities to favor narrow self-interest over “doing the right thing” according to traditional moral and ethical values. The permissive practice of insider stock trading by elected government officials is an egregious case that is currently under far greater scrutiny. Another is the gross inequality in corporate compensation whereby CEO’s pay has soared 1,085% since 1978 compared with a 24% rise in typical workers’ pay.[5] The attitude seems to be, “Well, everybody is doing it, so why not me?” as politicians race to keep up with the outsized wealth of their peers in finance and corporate America. These degenerate attitudes filter down and feed the deep resentment of the voting public.

This has become a greater concern as citizens begin to lose faith in democratic capitalism itself in favor of foggy notions of state-centered socialism. While the majority of Americans (a stable 60%) eschew socialism in general and the data can be confused by varying definitions of capitalism and socialism, we can see a worrisome generational decay of faith among younger generations that have never experienced any other socio-economic system.[6]

This chart of generational attitudes in the U.S. toward money are a good illustration of the deleterious psychological effects of money illusion. Gen Z, those born between the years 1997 to 2012, define financial success as an annual income of $588,000 with a minimum net worth of $9.5 million! This compared to a national average of $64,000 income and net worth of $1.1 million. There is going to be a very large number of disillusioned Americans just entering the age of political relevance.

Not surprisingly, the siren song of socialism also finds strong support from left-leaning liberal ideologies. This would compare in stark contrast to the opinions of those who have actually lived under centralized “socialist” societies. While ideological fashions ebb and flow, the true cost to capitalist societies is toward greater centralization and control of society at the margin. In other words, the true danger becomes creeping state control as a reaction to every economic crisis, gradually eroding personal freedoms and opportunity. We should not ignore these proclivities due to our failure to address the challenges we face as a free society.

D. Trade and Geopolitical Conflict

Global trade is subject to the fluctuations of the exchange rates for the currencies that each country uses to prices their goods and services. For example, as the US$ appreciates relative to the Euro, the US$ price of European goods imported into the US goes down while the Euro price of US goods exported to Europe goes up. This affects the supply and demand for traded goods that then affects the production and revenues of the producers of those goods. The impact is felt through employment and the macroeconomic fortunes of the trading nations. So ultimately, trade fluctuations become a political as well as economic issue.

Everything works to the mutual benefits from trade as long as it stays in balance. When trade gets out of balance—because countries have different trends in demographics, productivity, tax, fiscal, and monetary policies—there are different mechanisms to get back in balance. Under the gold standard it was the exchange of gold reserves; under a floating exchange rate system it’s through adjustments to exchange rates and international borrowing mechanisms. But exchange rate adjustments have disparate effects across domestic economies, which means some industries benefit while others pay the cost. This becomes a political conflict between winners and losers associated with globalized trade. Under a fiat currency regime, governments usually address these conflicts with the path of least resistance, which is fiscal deficit spending and borrowing. Hence the explosion of sovereign debt in the world today. To compound the problem, most international borrowing is contracted in US$s, meaning borrowers have no control over the value of those US$s they are obligated to repay.

Unfortunately, there are limits to such policies and countries that are more trade-dependent with weaker currencies reach those limits sooner. What unfolds is a collapse of the country’s currency, creating domestic social and political turmoil. Countries are faced with default on their sovereign debt that then cuts them off from future credit and/or must impose austerity measures on their populations that can lead to social upheaval with governments collapsing. These countries are between a rock and a hard place and the crisis can easily spread to military conflicts with coups and hot wars.

US monetary policy managing the US$ is particularly relevant here due to its role as the global reserve currency that dominates global trade markets and global monetary reserves. Over the period 1999-2019, the US$ accounted for 96 percent of trade invoicing in the Americas, 74 percent in the Asia-Pacific region, and 79 percent in the rest of the world. The only exception is Europe, where the euro is dominant with 66 percent. The US$ also comprised 58 percent of disclosed global official foreign reserves in 2022, far surpassing all other currencies.[7]

What this means is that not only is the US economy dependent on the US$, so is the rest of the world, which means in order to trade on a global scale, other countries need to hold US$s. This makes them dependent on the supply of US$s in the global financial system. As previously stated, many US$s are held outside the US and most of the international borrowing and lending is conducted in US$s outside the US banking system.

When the US$ appreciates or depreciates against other currencies, the financial consequences, both good and bad, reverberate throughout the global economy. When the US$ appreciates, foreign borrowers must service their US$ loan obligations by selling their own currencies or assets to buy dollars in order to pay their debts. What’s good for the US economy and financial system is often very bad for developing countries and even developed countries, as explained previously. Mismanagement of the US$-based global financial system can ultimately lead to wars, social crises, political collapse, regime change, and mass migrations.

As of July, 2024, 92 countries were estimated to be in sovereign default, unable to service their debts or refinance, with 60% of low-income countries at high risk of debt distress.[8] In 2024, 74 countries representing half of the world's population held national elections. Many of them, including the US, saw a replacement of the ruling incumbent by the opposition. This is one ‘canary in the coal mine’ revealing the general public discontent with political and monetary mismanagement of the global economy.

[1] F.A. Hayek, The Fatal Conceit

[2] The “interest rate” balances the past, present, and future in order to maintain stability for civilizations to prosper. See Common ¢ent$: A Citizen’s Survival Guide to Finance+Economics+Politics.

[3] “Trends in Income From 1975 to 2018” https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WRA516-1.html

[4] https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/trend/archive/fall-2024/americans-deepening-mistrust-of-institutions

[5] https://www.epi.org/publication/ceo-pay-in-2023/

[6] In one survey of Western democracies, the total agreement (strongly agree and agree) that socialism is the ideal economic system amongst the 18–34 age cohort ranged from 43 percent in the United States to 53 percent in the United Kingdom. https://jacobin.com/2023/03/socialism-right-wing-think-tank-polling-support-anti-capitalism

[7] https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/the-international-role-of-the-us-dollar-post-covid-edition-20230623.html

[8] https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/SAN2024-19.pdf https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/12/13/developing-countries-paid-record-443-5-billion-on-public-debt-in-2022#:~:text=Surging%20interest%20rates%20have%20intensified,distress%20or%20already%20in%20it. Admittedly, much of this sovereign debt can be attributed to the global pandemic as countries were forced to deficit spend to support populations while global production was shut down. But the fact that much of the debt is denominated in US$s makes it that much more difficult and precarious for governments to service these debts or obtain new credit.