This is the third installment of this three-part essay. Part One is here. Part Two is here.

PART THREE

I. Conclusion

As Keynes explained in The Economic Consequences of the Peace, money illusion through currency devaluation and inflation is a phenomenon that is both stealthy and difficult to comprehend. It works for the interests of a few and against the interests of many. We have discussed some of the primary negative consequences but in summing up it may help to draw from some real-world anecdotes that illustrate how our personal experiences relate to higher level policy actions and macroeconomic phenomena.

1. Price distortions – the biggest distortions we face today are the prices of houses and financial assets. Cheap credit has flowed into these assets, recapitalizing them at much higher levels with little change in real value. Housing prices have figuratively “gone through the roof” and homeowners are partly deceived that this has made them rich (somewhat true to the extent that people were able to use refis and HELOCs to increase their spending on luxury goods and services – but their debt principal is now higher while their debt servicing costs have stayed the same or declined).

The reality is that most homeowners still live in the same home but their carry costs have increased: property taxes, insurance, repairs, maintenance services have all skyrocketed in price with the increase in home values. So, who’s really getting rich? Median incomes have not kept pace with median home prices. Nobody really knows what a house is worth because price has diverged from real value fundamentals. Zillow is not reality – it’s an estimate priced at the margin.

The same is true of financial assets. The value metrics for financial assets like stocks and bonds have been distorted. Valuations are at historic highs. In a fiat currency world, historical comparisons may be inaccurate, but the higher investors pay for financial assets, the greater the risk assumed. So, what is a stock worth? What is a company like Apple or Facebook worth? Price doesn’t really tell us.

Money illusion also inflates the prices of collectibles and luxury goods. The price of a luxury car now exceeds what the median house price was 30 years ago.

Lastly, and most important, money illusion has made services in healthcare to be priced in fantasyland. Setting a broken arm now incurs a $40,000+ fee? Your hospital room now costs over $5,000 per night? None of these “bills” ever get paid in full and the sticker price is a complete fiction. How does this help us rationalize healthcare and insurance costs?

2. Asset bubbles – as stated above, the biggest asset bubbles have been in housing and financial assets since these are leveraged with low-cost credit. Money illusion forces a divergence between the real and nominal values of these assets, but our perceptions are shaped by nominal values. With financial assets, the higher the price signal, the greater the FOMO demand, dangerously increasing the overall systemic risks to the markets. Look at meme stocks and crypto tokens and AI-anything. Such euphoric behavior driving resource misallocation corrects at great costs to society while wiping out individuals along the way.

The price bubble in residential housing is probably the most significant indication of asset inflation. Buying a house now is more than fulfilling a simple need for shelter; it can be a life-changing risk if one times the market wrong, or it puts far too much of household wealth in one risky asset, as wildfires in California have recently demonstrated.

3. YOLO and FOMO – in a commercial economy, every economic incentive is geared towards conspicuous consumption and instant gratification (re: the advertising industry). Subsidized interest rates powered a credit and consumption bubble that characterized most of the years between 1982 and 2022, and it continues at the high end. Money illusion’s “free money” along with cheaper trade goods from China and other low-cost manufactures exporters have habituated most people in the developed economies to a never-ending orgy of spending on consumer goods and services paid for by debt claims on the future. Social media has only intensified human behaviors like FOMO and YOLO.

Unfortunately, these behaviors, which look good in GDP and employment headline statistics, pull future consumption demand forward, while increasing debt obligations in the future. The lack of saving, investment, and asset accumulation in favor of spending increases the wealth divide between the haves and the have-nots. Some observers have coined these times as a return to neo-feudalism, where the producers accumulating the benefits of money illusion are the new landlords and those who overspend end up serving as their serfs. In 2023 consumer credit card debt exceeded $1 trillion. How many people today carry credit card balances while paying exorbitant interest rates?

As we will explain below, this consumption bubble has greatly distorted prices across economies and prevented the natural cycle of consumption, savings, and investment that keeps economies in equilibrium over time with the natural ebb and flow of demographics and technological innovation. Thus, we get massive imbalances in trade and capital flows that impede countries’ growth prospects.

4. Economic Inequality – asset bubbles driving inequality has mostly affects those who work for a wage and must save to buy a house; two needs that fall disproportionately on younger generations and low-income classes. We’ve seen CEO compensations soar to stratospheric levels while median employee incomes stagnate. The tax structure aggravates these disparities by overly taxing incomes (the getting of wealth) relative to taxes on wealth itself.[1]

The US Treasury also benefits from real asset bubbles caused by money illusion as proportional taxes increase while real values stay the same. If your house price doubles merely due to inflation, the capital gains tax at a sale does not account for inflationary gains as opposed to real gains. So, tax revenues rise at the expense of asset owners. As previously mentioned, property taxes also increase, which benefits state budgets. This applies to any other financial asset you own. Taxes are based on nominal values, not real values and as Keynes asserts in the opening quote, inflation enables authorities to impose a hidden inflation tax.

5. Inflation – consumer price inflation is probably the cost of money illusion easiest to observe in everyday life. It can also be hidden through the manipulation of official statistics. We’ve seen all essential cost of living items rise rapidly in price over the past few years to the tune of 12-25% and sometimes higher. Relative price changes are a natural occurrence as supply and demand for particular goods and services adjust. But a rise in the general price level across all goods and services reveals a true devaluation of money. Unfortunately, the official protections against inflation for wages and fixed incomes are based on manipulated statistics like the Consumer Price Index that understate the prices of energy and food. It also fails to fully measure asset price inflation. So, inflation is low as long as you don’t need to eat, buy a house or car, go to college, save money for retirement, or use any energy!

Official statistics also underestimate unemployment and often overstate GDP growth.[2] The political incentive is not necessarily to deceive citizens as it is to create a sense of confidence about the economy due to its positive effect on behavior: confidence in the future leads people to invest and produce more; to take more risks and innovate. These reasons may seem valid, but none of them defend against the real social and economic effects on consumers and citizens.

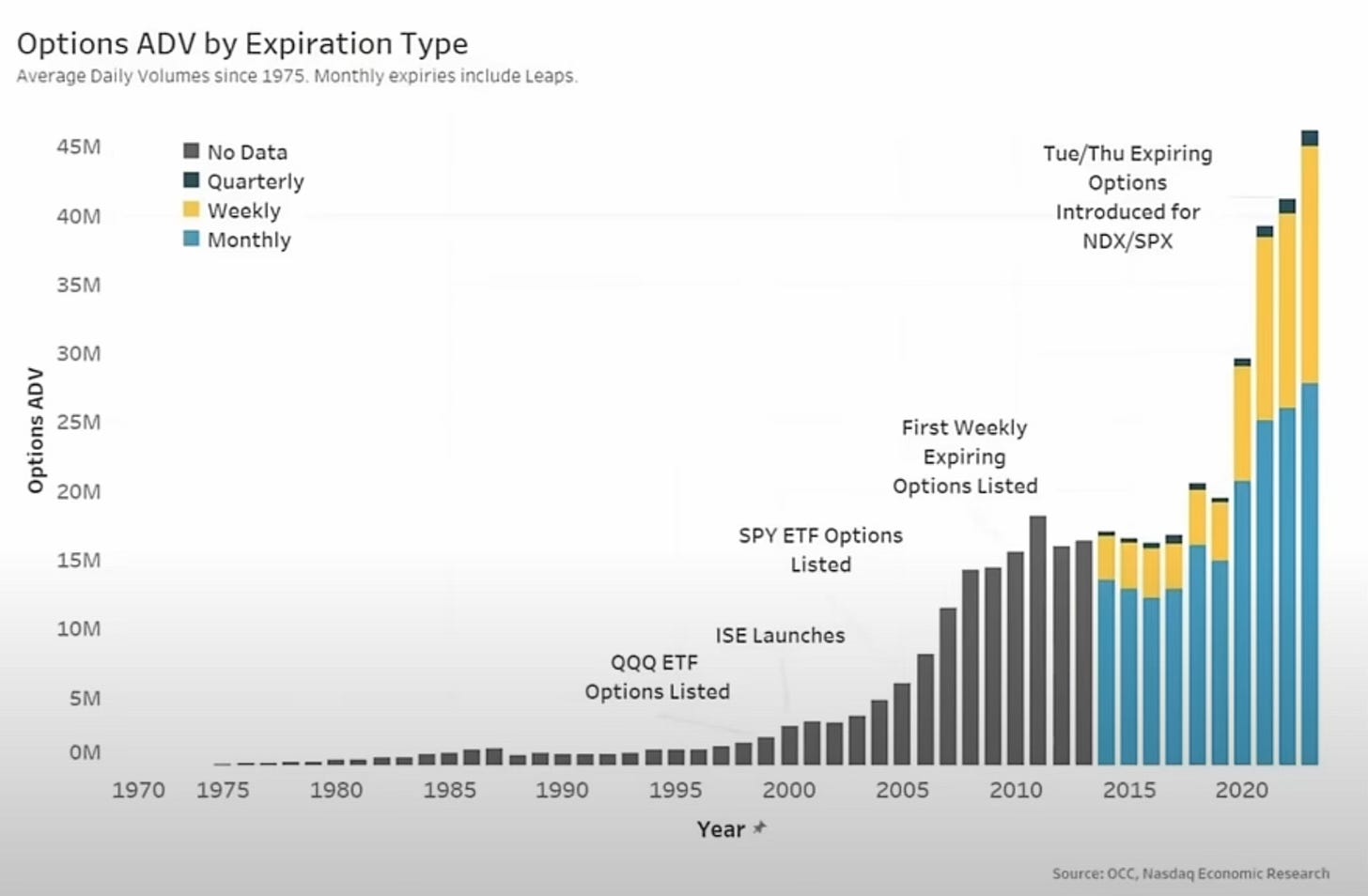

Financial risk – when prices diverge from value under money illusion there are many opportunities for speculation and arbitrage among assets and across asset classes. The Great Financial Crisis of 2008/9 demonstrated the risks of financialization with securitization of mortgages and the upsurge of financial derivatives keyed off every asset class. Securitized mortgages enabled lenders to off-load the risks of housing loans while exotic derivatives like credit default swaps allowed hedge funds and banks to bet against the housing bubble. Yet, since the GFC the leverage provided by derivatives such as stock options has exploded (see chart below). This accelerating leveraged financialization highlights the dominance of the global financial sector as it has leap-frogged traditional industry as the driver of the modern economy. Not only are wealth effects from asset markets now crucial determinants of spending, but their whopping indebtedness now makes governments’ interest payments a key source of income for the private sector. In fact, capital markets themselves are no longer systems for raising new capital, but have become vast mechanisms for speculating on asset price volatility and refinancing these huge accompanying debts. The Federal Reserve has become the tail that wags the dog of the real economy.

Granted, the financial industry is in the business of managing risk and creating new products to facilitate risk management through trading markets. But when fixed income investments and cash savings accounts are earning close to zero, pension systems and retirement funds need to “chase yield,” assuming greater risk in order to meet their funding obligations. We refer to the suppression of interest rates as financial repression and it forces riskier investing for savers and retirees dependent on interest and fixed incomes from pensions and Social Security. When investment cash flows decline to zero, investment returns must be realized by price changes and capital gains through trading. This increases price volatility and investment uncertainty, all leading to the systemic risk of contagious booms and busts. Finance evolved to manage and reduce risk, not increase it. Not only were savers not earning any interest income from banks, money markets, or US Treasury bills over the past decade, they have been exposed to much greater systemic risk of a market crisis, risking losses they may never be able to recover.

6. Trust – as mentioned in the Introduction, modern democratic societies across the globe have suffered a loss of trust in their governing institutions. In the US, this loss of confidence in democratic politics has been acute among younger generations:

As part of the online poll of 943 18-30-year-old registered voters, participants to responded to a series of questions about the American political system: 49% agreed to some extent that elections in the country don’t represent people like them; 51% agreed to some extent that the political system in the US “doesn’t work for people like me;” and 64% backed the statement that “America is in decline.” A whopping 65% agreed either strongly or somewhat that “nearly all politicians are corrupt, and make money from their political power” — only 7% disagreed.[3]

The extreme divisions along partisan lines within the political class, party leadership, and media platforms has sown this mistrust more broadly to the point where different factions listen to their own media sources and create their own political narratives that describe widely conflicting universes.

We experience these conflicts in elections with the two major parties fracturing into separate wings at the same time that party identities have weakened. This political dysfunction has opened up the electoral landscape to anti-establishment populist movements of both the left and right. The campaigns of both Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump reflected this populist shift against the establishment.

Excess government deficit spending enabled by money illusion has allowed waste and political patronage to increase in both the private and public sectors. In the private sector we find many cases of corporate welfare and subsidies at the same time these corporations post record profits and CEO pay increases. In the public sector the hidden spending on NGOs and other political activist groups is being uncovered by the promise to rationalize the Federal budget under the auspices of the Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency. The exposure of patronage has gone viral on social media and this accounting has been strongly supported by Trump’s populist majority. This is just one more factor reducing trust in government and bureaucratic institutions due to reckless spending.

On the ideological dimension, the loss of trust in democracy and markets has increased flirtations with alternative political-economic systems such as democratic socialism, or full-bore socialism, or even benign authoritarianism. One can easily get lost in the weeds here because most Americans have little experience or education about non-capitalist ideologies. The media provides little clarity in defining these systems, mislabeling them as communism, fascism, welfare capitalism, regulatory capitalism, or social democracy. But the general difference is over whether the loci of ownership and control of resources and enterprises should reside in the state or the private market. In fact, the US and all the world’s democracies have mixed systems, with legal and regulatory constraints on private markets. But the tendency can be for populists to demand state control during times of crisis, even though state control has never been proven economically efficient or politically popular.

The confusion over ideology really comes down to how societies adapt to change and how they distribute the costs and benefits of that adaptation, or lack thereof. This becomes a matter of trade-offs and democracies can manage differences of opinions negotiated through voting while regulated markets can manage the rational allocation of resources. But any mistrust in voting processes can sow discord and inhibit the stable functioning of a free democracy.

On a deeper, long-term trendline, this is all a reflection of political discontent with the status-quo – a status-quo shaped by money illusion under misguided monetary and fiscal policies over the past half-century. As Jim Rickards states, “Money’s value springs from trust, and trust itself depends on some institution— a central bank, a rule of law, a gold hoard, an AI algorithm— to sustain it. When institutions break down, and trust is lost, the value of money is lost as well.” This is seconded by economist Judy Shelton: “Much of monetary policy is based on money illusion making people feel like they're gaining (when) they get a nominal raise. …The whole idea of a 2% inflation target is that you could have an economy decline and everyone might have to take say a 1% cut but if you have 2% inflation you can actually give everyone a 1% raise and they think they're ahead of the game even though they're now losing in terms of not being able to keep up with the inflation. I think that's a basically very dishonest approach.” [4]

Ultimately, when consumers see how capitalists are able to accumulate wealth while they suffer from inflation, they become hostile towards the existing system in place. Yet it is not the system that is at fault, but rather how we have distorted that system with poor policy choices. As Lenin declared, the best way to destroy the capitalist system is to debauch the currency.

7. Geopolitics – lastly, we have the most destructive threat of global conflict, social and political chaos, and war. When countries practice money illusion through currency manipulation, the exchange value of currency fluctuates, which can make it difficult to maintain the relationships between cross-border debtors and creditors. Trade and financial imbalances, instead of reverting back to equilibrium, can rise to critical levels. It can also make it extremely difficult for countries dependent on external currencies to manage their own economic affairs, usually forcing them into politically unacceptable choices with unfortunate social consequences, like currency devaluation or austerity. This foments domestic social conflict and institutional collapse that can lead to political chaos, sometimes resulting in violent coups, regime change, or imperialistic ventures. The danger is that large wars, i.e., world wars, usually start with smaller conflicts.

We have seen this unfold in the Middle East with Iran and Syria. While we cannot attribute Middle East unrest that has engulfed the region solely to economic and financial imbalances, the conflict over oil that is priced in US$ is certainly a major factor mitigating against regional autonomy and stability.

The European Union, however, is an excellent illustration of political conflict related to currency policy issues. The southern European countries—Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece—have been disproportionately affected by the currency union under the Euro and the European Central Bank (ECB) and have gone through several phases of regime change due to sovereign debt crises. Regime change has also crept north and east as nationalist parties have gained public support in France, Germany, Italy, and Hungary. In otherwise stable political democracies we’ve how voters have registered their dissatisfaction with the politics of long-standing political regimes. Most notably, the UK experienced their populist revolution with Brexit, its withdrawal from the European Union. Much of this has been related to mass migration from those peripheral states in the ME and North Africa that results from political and economic unrest in these regions. In India we’ve seen the rise of the right-wing, nativist BJP party. Then we have the Russian invasion and current war in Ukraine, which was most certainly related to the flagging economic fortunes of Putin’s regime.

The least noticed but probably the most significant consequence for global stability is the gross imbalances between the developing and developed world as a result of a combination of mismanaged central bank policies and Chinese mercantilism. Chinese mercantilism has denuded competing developing countries of their labor-intensive manufacturing industries, while US$ policy has restricted developing countries’ access to capital, leading to excessive debt burdens priced in US$. The double whammy reduces national income while devaluing their capital base, causing a debt-credit crisis. The result has usually been political and economic collapse. We’ve witnessed this most acutely in Central and South America. Argentina finally hit a wall of dysfunction, heralding in the populist, libertarian reformer Javier Milei as president, promising drastic austerity to restructure the Argentine economy and fiscal regime.

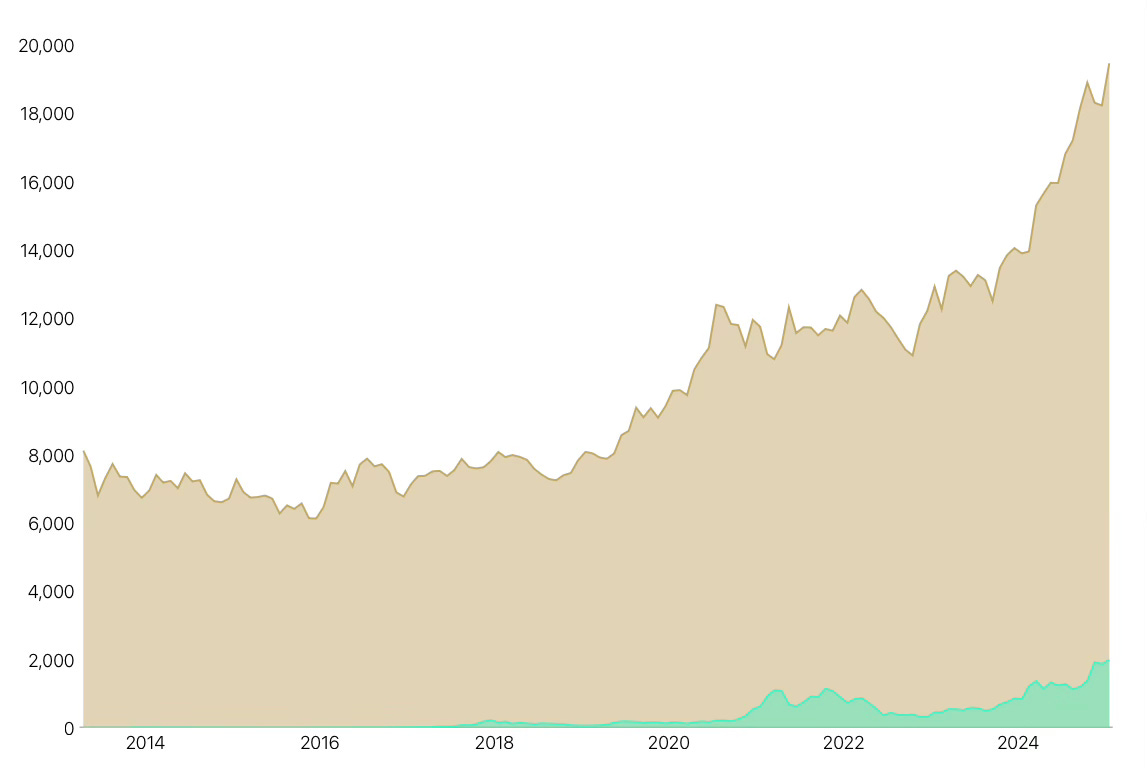

This cascade of disorder and mistrust of monetary policies is reflected in the markets for precious metals, particularly gold, and bitcoin as the dominant cryptocurrency. In times of productive wealth creation these alternative “hard money” assets are devalued relative to more productive assets, like public companies with increasing profits. But political unrest and economic uncertainty related to the perception of currency devaluation causes funds to flow back into these assets, which are now at all-time highs.

Market Capitalization of Gold and Bitcoin, in US$ billions

8. Culture – I saved this category for last as I would speculate that money illusion and cultural degeneration go hand-in-hand and mutually reinforce a downward spiral. As previously stated, money has a corrupting influence on behavior and free money amplifies this corruption on a grand scale. This applies to every human element as the spoils system permeates through every aspect of our society, from politicians to bureaucrats to public servants to unions to corporate suites to educational and health institutions to media and entertainment, and sadly, even to religious institutions. Moral and ethical rectitude becomes in short supply as most people naturally adopt the rationalizations of “everybody is doing it,” or “that person is getting rich, why shouldn’t I?” or “It’s the way the game is played, I need to keep up.”

In the US we have become obsessed with the mixing of political and popular culture. Partisanship or ideology notwithstanding, it has become one tribe against the other. Citizens object to the crassness and lack of decorum in their leaders, not only in politics but across all society’s elites, but don’t these leaders merely reflect that same behavior in the popular culture? And how did the popular culture degenerate to such levels? I would suggest it’s all about free money and the devaluation of prudence, hard work, and accountability.

I end here to note that the road back will require returning money to its honest and trustworthy role as a proxy for the productivity of time and energy. Ultimately, sound money is not only a functional imperative but a moral one as well. It is said that money is one of the foundations of civilization while the price of money, as denoted by its real value and the interest rate, is said to be the most important market price. Manipulating the value of money through illusions is cheating. Returning money to its proper role would also reinstate credit as a hard constraint on human behavior that forces people to be prudent, responsible, and accountable.

Rediscovering normality in credit markets implies price resets to asset markets that would be accompanied by a severe economic correction, whether a recession, market crash, or depression. We’ve come to the point where such corrections are politically unacceptable, even if economically inevitable. This means unprecedented political interventions can be expected that will have arbitrary consequences across society. We can expect the can to be kicked down the road until the point where the road ends at a cliff. Thus, the eventual reckoning may herald not only a political and/or economic crisis, but also an existential spiritual one. Most religious doctrines warn of the corruption of money and materialism and its dire consequences—a common occurrence of civilization.

Students of such societal crises have developed a thesis of “turnings,” where generational cohorts cycle through four phases over the period of a lifespan: prosperity, awakening, unraveling and crisis; after which the cycle starts anew. They argue that we are currently experiencing the unraveling before the impending crisis in what they refer to as the Fourth Turning.[5] Of course, to quote a popular Yogism: “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

Lest we think we are at the mercy of evolutionary forces, I argue that there is a lesson to be gleaned from recurring crises and the cycles of boom and bust. A boom is a phase when circumstances and behaviors lead to positive outcomes—think of a Renaissance. During this phase success breeds success and concentrates the ownership and control of productive assets. In simple terms, the rich get richer and the poor get by, with maybe a pay raise. But as circumstances change in a universe of constant change, those behaviors fail to anticipate or adapt and we get to a point that Former Fed Chairman Greenspan described as “irrational exuberance,” where hidden risks can become systemic. As the Powers That Be consolidate their hold on power in the face of decline, the economy and society become less resilient and adaptive, becoming, in the words of author and financier Nicholas Taleb, more “fragile.” That can be when an unknowable unknown event—a black swan in Taleb’s terminology—strikes that the system cannot manage, throwing it into crisis and chaos, or the bust phase.

This is a recurring cycle in civilization that could be managed if we focused more on building societal structures that were both anti-fragile and adaptive to change. This will require a better understanding of the economic dynamics together with public policies and institutions consistent with adaptation (such as monetary finance). For example, equity finance diversifies risk while debt increases and concentrates risk and return. Leveraged debt merely magnifies this divergence between debt and equity. Collateralized lending favors those who own the collateral. Since 1996, due to debt-financed buy-outs, mergers, and privatization, the number of public corporations listed on the stock exchanges has shrunk from 8025 to 3600 today. This shift from equity to debt reduces the opportunities for broader participation in the capitalist wealth-creating process.

Monetary policy has also affected the relationship between labor and capital. While our tax and labor policies with mandatory benefits have increased the expense costs of labor to employers, the Fed’s ZIRP and QE policies reduced the cost of capital to virtually zero, causing companies to substitute cheap capital for expensive labor. We see this every day at the retail self-checkout counters. This tax on labor has only increased due to uncontrolled border migration. Finally, we’ve tried to compensate the growing inequality by increasing tax and redistribution to those most affected, but this just violates the old proverb to prevent dependency: Give a man a fish and he eats for a day; teach a man to fish and he eats for a lifetime.

These are only a few examples of how we have moved in the wrong direction on monetary and fiscal finance. The challenge will be to reverse this decades-long trend and move in the opposite direction to secure a more resilient and adaptive free society.

We’re nowhere near that point yet.

[1] I do not mean to imply we should tax wealth, but rather recalibrate the taxes on production versus consumption. This may only be accomplished with a progressive tax structure on capital and wealth, not across-the board increases on taxes on production, i.e. income.

[2] https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2025/02/11/democrats-tricked-strong-economy-00203464

[3] https://www.semafor.com/article/05/28/2024/a-dying-empire-led-by-bad-people-poll-finds-young-voters-despairing-over-us-politics

[4] https://www.theinstitutionalriskanalyst.com/post/jim-rickards-the-treasury-should-buy-gold;

[5] https://www.amazon.com/Fourth-Turning-American-Prophecy-Rendezvous/dp/0767900464/